Labour Prime Ministers come across very well. Think of those acclaimed as some of Britain’s greatest leaders: Clement Attlee rebuilding Britain after the second World War and the creation of the National Health Service (NHS), increased aid and equality of the disadvantaged under Ramsay MacDonald, and even though the Iraq War casts a looming shadow over his legacy, Tony Blair is probably still the greatest Prime Minister of the 20th century – even if some of his greatest reforms took place in the 1997-1999 period. The UK has had six Labour PMs and one unfortunately not discussed enough is Mr Harold Wilson.

Was Harold Wilson Britain’s greatest Prime Minister? Here is a case for his place in history as the United Kingdom’s greatest leader.

Current Perception

Wilson’s reputation and ranking in terms of PMs has seemingly been revived over time. The most in-depth survey of British PMs of the 20th century was done by Ipsos Mori and the University of Leeds working in conjunction. In this, 139 academics used a 1-10 rating to rank the 20th-century PMs. Taken whilst Blair was in office in 2004, Wilson ranked 9th out of the 20 leaders, with a mean rating of just under 6 – reflecting the view he is as a decent, bread-and-butter PM but not one of great success.

This ranking was fairly similar to his rating in 1999 when 20 historians ranked him at number 10 (there is an obvious pun I could do here but somebody was always going to be in that position). This was in the lower half however as Blair was discounted.

He was given a good result when given 3/5 points in a ranking by historian Francis Beckett.

Polls by the University of Leeds in both 2010 and 2016 saw favourable top-five rankings. This was similar to a YouGov poll also which holds him fifth, with Wilson liked more than disliked or rated neutrally. He was also ranked here by a Newsnight 27,000-strong poll in 2008.

So overall, his tenure in office is seen as anywhere from decent yet unremarkable to a strong but not exceptional candidate for the top spot.

A Case For Britain’s Best Prime Minister: The Numbers

In terms of numbers, Wilson could very well be the best Prime Minister of Britain.

Not only did he become Britain’s youngest PM in seven decades but his parliamentary record based on statistics is a truly strong one. In 1947, prime minister Clement Attlee made Wilson – then aged 31 – president of the Board of Trade, securing his place as Britain’s youngest cabinet minister since William Pitt the Younger in 1782.

Firstly, Wilson won four general elections. This is tied for the most, being the only PM to do so in the 20th century, with the others being: Robert Walpole, Lord Liverpool, and William Gladstone. According to the Reviews In History website, he was the first occupant of Number 10 to increase his majority at successive elections.

His election wins are quite something. In 1964, Wilson narrowly beat out the Conservatives’ Alec Douglas-Home. With only 200,000 more votes (12,205,808-12,002,642 according to the BBC), 13 more seats (317-304) and 0.7% additional vote share (44.1%-43.4%), Wilson’s government scraped in a majority of four seats.

Two years later, Wilson was more successful, winning a chuffing 98-seat majority – winning over 1.5 million more votes than the Conservatives and over 100 more seats. Wilson’s government saw a 48% vote percentage, a record not matched since (discounting the 2010 coalition between the Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives). In the book The Impossible Office? The History Of The British Prime Minister, the authors described “Prime ministers in their most successful phases” including “Wilson until 1967.” Wilson lost in 1970.

In February 1974, a hung parliament result was returned for the first time since 1929. The 78.8% UK turnout has not been overtaken in the decades since. With nobody earning a majority, the Labour Party under Wilson actually got back into government despite a smaller vote share. This was due to a greater number of seats won. With that, Wilson formed his minority government. Wilson had become the first person except Winston Churchill to return to Downing Street; both won despite smaller vote shares under a flawed First-Past-The-Post system.

Later that year in October, another election took place – two of the closest elections in terms of time passing – which saw a majority…of three seats. Aided on by Labour’s end to the miners’ strike that had hindered Heath’s time as PM, Wilson won in a recession-weary decision for the nation.

Wilson resigned in 1976, having told an aide “I have been around this racetrack so often that I cannot generate any more enthusiasm for jumping any more hurdles.” Under stress and dealing with mounting issues such as potential Azheimer’s disease and colon cancer, Wilson announced in March 1976 his desire to retire from the role aged 60 the following month.

The Imperial and Global Forum documents that: “Gallup polls showed that almost 50% of voters were satisfied with his performance when he stepped down in 1976.”

A Case For Britain’s Best Prime Minister: Legislation Under Wilson

Chances are, if you know one thing about Wilson, it is the historically significant legislation created under his premiership.

No matter where you were worldwide, no nation seemed immune to the 1960s, perhaps the greatest era of cultural change, especially in terms of countercultural change. This was especially prevalent in the US with the Civil Rights movement, ‘Summer Of Love’, and the threat of nuclear fallout from the Cold War dominated the cultural sphere. The UK was not excluded and nor was the UK’s politics.

Sexual Offences Act (1967)

Perhaps the most important is the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, which decriminalised homosexuality. Historically, sexual acts between men had been punished severley, with the two most famous cases being that of playwright Oscar Wilde (who was sentenced to two year’s hard labour) and Engima codebreaker Alan Turing (whose forced chemical castration led to his suicide at just 41). Attitudes had someone changed by 1967. In 1966, the Earl of Dudley proclaimed: “[Homosexuals] are the most disgusting people in the world… Prison is much too good a place for them; in fact, that is a place where many of them like to go—for obvious reasons.” Even the rightist Daily Mail ran a poll in 1965 in which 63% thought homosexuality should be decriminalised, which is good; not so good however is 93% believed homosexuals needed medical or psychiatric treatment. This Bill was actually backed by some Conservatives such as Enoch Powell and rather surprisingly Margaret Thatcher.

The third reading saw a staggering 101-16 votes according to the UK Parliament website. The Bill only applied to males over 21, consensual, and in private. There was still a long way to go but Wilson’s government started the ball rolling on what the late, great Christopher Hitchens described as “not just a form of sex, [but] a form of love.”

Race Relation Acts (1965, 1968)/Sex Discrimination Act 1975

In an increased time of racial tensions, Wilson’s government introduced the Race Relations Acts in 1965 and 1968, which were a step forward in the increased legislational banning of racial discrimination in the UK. This, alongside the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, proved how the government tackled topical issues and patched up areas of discrimination in British society.

Equal Pay Act (1970)

The Equal Pay Act 1970 was a culmination of a 1964 Labour manifesto promise for equal pay. By the late 1960s, polls showed about ¾ of those asked supported equal pay between the sexes, devoid of gender. Not just in terms of wages but also pensions, holidays, bonuses and the like.

A “very significant part in the history of the struggle for equal pay” according to MP Shirley Summerskill for this was the Ford machinist strike of 1968 in which a series of skilled women dropped tools, per se, after learning they were going to be paid 15% less than their male counterparts.

It was not just legislation that put forward gender equality rights but also one that put Britain amongst European neighbours.

Abortion Act (1967)

In 1967, the Abortion Act was passed. Although backed by the government and with the committee chaired by John Peel (no, not that one – actually a leading British gynaecologist), this was a Private Members Bill from Liberal MP David Steel. Similarly that year, the National Health Service (Family Planning) Act was passed which allowed NHS-available contraception.

14% of maternal mortalities were from abortions but now, desperate mothers can have their worries quashed with safer abortion treatments via the NHS. Such is a reason for Wilson’s time as PM being known as “The Golden Age Of Welfare State”.

Representation Of The People Act (1969)

Wilson introduced the Representation Of The People Act in 1969, which allowed 18-year-olds and upwards to vote. Previously only people over 21 could vote. Ironically, Wilson lost the following election. In this era, it was more common for youths to differ or speak out perhaps against their parents’ wants and want renewed liberties.

Murder (Abolition Of Death Penalty) Act (1965)

Wilson also prohibited capital punishment under the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act 1965.

Execution grew more contentious by the end of the 1960s, especially with wrongful or highly-controversial killings of the likes of Timothy Evans (hung but later revealed to not have killed his wife and daughter of which he was convicted) and Derek Bentley (whose friend, then a minor, shot a police officer after a questionable prompt). Writer and comedian Charlie Brooker wrote of the death penalty: “Capital punishment is supposed to act as a deterrent, but it doesn’t seem to have much effect on crime statistics. This is because most current executions a) employ methods that are as quick and efficient as possible and b) take place behind closed doors – almost as though the people doing it are ashamed of themselves.”

Rejected as a PMB in 1956, Labour’s Syndey Silverman passed the Bill with a five-year shelf life with further provisions needed prior to July 31st 1970 when it would expire. In December 1969, resolutions were passed and the death penalty was abolished permanently. No executions in the same style have appeared since.

Theatres Act (1968)

The 1968 Theatres Act abolished stage censorship in the UK.

Scripts had been licensed for performance since 1737’s Licensing Act as a way of preventing political satire of Britain’s then (and inaugural) PM Robert Walpole. The Beggar’s Opera by John Gay, the second-longest-running theatre production at the time, satirised corrupt politicians and was likely a leading cause of this ban. This had been argued against notably in 1909 with a joint Select Committee featuring Peter Pan creator J.M. Barrie and future Nobel Prize for Literature winner George Bernard Shaw.

Wilson’s government finally terminated the need for licensing in 1968.

In addition, government cultural expenditure exploded from £7.7 million in 1964 to £15.3 million within five years.

Divorce Reform Act (1969)

The 1969 Divorce Reform Act, only given ascent after Wilson left office, allowed a relaxing of conservative value legislation. This notably allowed a ‘no fault’ reasoning for divorce in which the individual did not need justification (such as adultery) to explain the grounds for divorce. This allows for greater freedoms of individuals without a life committed to a partner.

Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act (1970)

The PMB Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act 1970 was passed by Labour’s Alf Morris, which gave greater facilities and aids to those with disabilities, allowing provisions for travel, food, and recreational services. Although Wilson played little part in the act itself, when back in power in 1974, he placed Alf as minister for the disabled – a newly-created position, the first disabled minister in the world. Earnings-related benefits were too given to the sick under Wilson, amongst other echelons of society.

A Case For Britain’s Best Prime Minister: Public Image

Wilson is probably the most working-class prime minister Britain has had, with a satisfying rags-to-riches story.

In a refreshing differing from the common Eton origins (of which 20 PMs have been), Wilson was an out-and-out northerner, born to a chemist father and schoolteacher mother in Yorkshire.

A quote from Ben Pimlott’s 1992 biography states that a 10-year-old Wilson told his mother, “I am going to be prime minister.”

Wilson spent years whittling away before premiership, including as a Cabinet and Shadow Cabinet minister, in the former of which he was the youngest of the 20th century at just 31 when appointed President of the Board of Trade. This previous establishment in the limelight gave legitimacy and credibility to the future PM.

Wilson’s image helped his popularity with his placement as party leader leading to a Gallop poll showing a 15.5% lead prior to the 1964 general election. Everything about Wilson was meticulously planned for the best public image. A 1964 interview from wife Mary Wilson saw her tell The Sunday Times about Wilson’s working-class, everyman image describing his food tastes and cooking expertise, especially his fondness of H.P. Sauce. A 20% lead resulted.

Upon becoming PM in 1964, Wilson remarked: “I still can’t believe it,” he claimed. “Just think, here I am, the lad from behind those lace curtains in the Huddersfield house you saw – here I am about to go to see the Queen and become prime minister…I still can’t believe it.”

One story follows that Wilson carried around a photo of Her Majesty in her wallet. Indeed, despite presumptions that the social dichotomy of two would lead to friction, the opposite seemed to be true. He was a regular face at Balmoral, invited to picnics, and even had meetings weekly that would exceed two hours, via The Sunday Post. This was reciprocated with the Queen making her first Downing Street visit in over two decades for Wilson’s departure dinner.

It is generally stated that Wilson was one of the Queen’s favourite PMs during her lengthy reign, during which she saw 16 leaders. Wilson described “relaxed intimacy” as he broke protocol with Her Majesty, even allowed to smoke his pipe and stay for drinks.

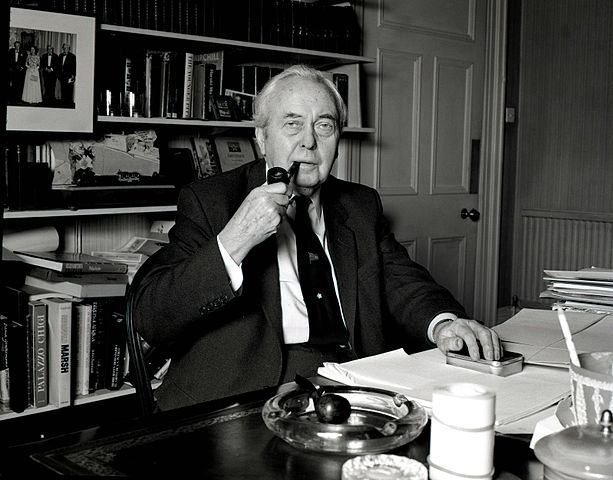

One of Wilson’s more public nuances was his penchant for pipe smoking. Wilson would rarely ever seen without a pipe. He was crowned the Pipesmoker Of The Year in 1965 by the British Pipesmokers’ Council.

It also helped that he was a strong speaker, able to resonate with the public, described by one commentator as “a magnificent orator, both in the Commons and at public meetings. He destroyed both Alec Douglas-Hume and MacMillan at the dispatch box and Edward Heath never matched him.”

This factored in with his famous and endearing sayings and ‘isms’, including the line: “A week is a long time in politics.”

Ex-Labour MP Roy Hattersley pointed out: that Labour Gallop polls showed: “64% of the sampled public described him as “likable”. Only 7% disagreed.”

As Wilson’s secretary Baroness Falkender, Marcia Williams, put it: “He was on your screen, he was in your home, and you could identify with him.”

A Case For Britain’s Best Prime Minister: Aberfan

We have separated this into a separate section, having covered the hugely melancholic Aberfan Disaster before.

The 1966 Aberfan Disaster was the resultant of coal disposal neglect, leading to a 30-metre high wave of coal containing two million cubic metres fell into the town of Aberfan below, killing 144 people; 116 of those killed were children.

Wilson arrived in Aberfan the same day, with the event being one of the first tragedies of the television aid. It is notable how quickly Wilson got to the scene, arriving in 12 hours, compared to the Queen, who did not step foot in the Welsh village for eight days – something she apparently cited as her biggest regret.

Wilson immediately set to work to right this wrong. Wilson allowed Secretary of State for Wales Cledwyn Hughes to “take whatever action he thought necessary, irrespective of any considerations of ‘normal procedures’, expenditure or statutory limitations” according to a Guardian newspaper at the time.

It was quickly established that a enquiry should be created, with Wilson making a speech in parliament a few days later: “It is expedient that a tribunal be established for inquiring into a definite matter of urgent public importance viz. the causes of, and all the circumstances relating to, the disaster at Aberfan, Merthyr Tydfil, on Friday the 21st day of October 1966.”

Wilson called the subsequent report “devastating.”

In reaction, the PM ensured nothing like this could or would ever happen again. I’ve written before about how many forms of the handling of the outfall of this disaster was fumbled but (as written previously) “Wilson’s government did quickly write up the Mines and Quarries Tips Act of 1969 to prevent another incident of this magnitude – but of course, it was too late to stop this, even if it could stop other Aberfans.”

His visit was still significant, showing true concern for the Welsh populous, fighting when able to ensure it would never happen again.

Wilson is said to have claimed about the day of the Aberfan Disaster in October 21st 1966 that it was “probably the worst day of my life.”

A Case For Britain’s Best Prime Minister: Vietnam Evasion

If there is one thing that defines a premiership, it is a botched military conflict; Tony Blair’s Iraq invasion serves as an example of this. One person to not back down to US pressure for intervention was contemporary Wilson.

In terms of the most controversial wars, an immediate go-to is the Vietnam War, in which growing youth opposition saw heightened domestic tensions to the government, including President Lyndon B. Johnson. The president was subject to effigy hanging and the popular chant: “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?”

It was Harold Wilson who was PM during the time that the Vietnam War tensions rose on the global stage. Protests also took place in Britain including a 10,000-strong protest in London in March 1968, with citizens seeing Britain as supportive of US actions, with Wilson not wanting to “kick our creditors in the balls.” Yet the UK never dipped its toe into Vietnam, with Wilson largely responsible for this.

Despite the UK’s economic hardship and US promises for economic aid if the British sent troops, Wilson was adamant for a non-interventionist policy. In a top secret letter from the prime minister to the president, Wilson wrote that: “My decision on my policy here is dictated not by political pressure but by what I know to be right.”

This naturally hindered UK/US relations, compounded further by personal dislike between the powerhouse executives, an issue further hindered by Britain’s withdrawal of bases from east of the Suez when Soviet communist spread was causing US paranoia.

Now, this is not to say the UK were entirely opposed to military conflict, with Britain wrapping up a military conflict in Borneo about a year before the 1967 Summer of Love, not to mention low war morale after two World Wars and the Korean War that within the past half a decade. Another factor is the aforementioned weak British economy, which would have prevented the necessary influential amount of aid. As biographer Rhiannon Vickers wrote: “The US Administration and President Johnson repeatedly demanded that Wilson commit troops to the Vietnam War, but he steadfastly refused to do so.”

Although the resistance put great strain on relations between Britain and America, there can be little argument that history will forever look favourably on Wilson for his decision.

A Case For Britain’s Best Prime Minister: Modernisation Of The Nation

Wilson is highly credited today for creation of the Open University, something the man himself has called his greatest achievement as PM. After receiving his honourary degree, Wilson remarked, “Everywhere I go in the world they want to know about The Open University and I’m very proud to be asked.”

The idea had been one Wilson had had even before election, seeing the disparity of higher education between higher and lower income households, working to find a way to allow the poorer members of society the rights to an equal and fair education, a famous 1963 speech saw Wilson comment on the “White heat of technology”, in which he proposed a so-called university of the air, with the OU going online many decades later.

Minister of Arts Jennie Lee was too significant in bringing Wilson’s vision into reality, overcoming vast opposition to the idea. Without Wilson, there would probably be no Open University at all – and he’s rightfully proud of that fact!

In a similar vein, Wilson was also a great housing innovator of his age. Via the Red Brick blog, Wilson achieved the best housebuilding figures of the last century. Wilson hit a peak in both public and private housebuilding at the same time, with “over 400,000 new homes in one year.” The 1966 manifesto pledged an even more impressive 500,000 and although only successful in pulling off 4/5 of this number, it is still incredibly impressive and unprecedented. This shows just how committed to social justice and equality Wilson was, desiring large-scale construction to aid people in the modern world.

That same website saw Steve Hilditch write: “He set a tone for Government, he oversaw radical commitments in manifestoes and he worked diligently to deliver them. Both the commitments and the delivery put our current politics to shame.”

Wilson also modernised legislational matters, with the first major British nationwide referendum. 1975 saw the again-elected Labour leader employ direct democracy in allowing the electorate a referendum on UK membership to the European Economic Community (EEC), the precursor to what is now known as the European Union (EU).

The reasons for this however were slightly dubious, with biographer Ben Pimlott writing: “He knew that if he brought Britain out, Roy Jenkins and his followers would be off – yet if he stayed in, he would offend Benn, Shore and Silkin. But they had no other hole to go to”. Effectively, the referendum was called so Wilson had an out-clause in order to not cause Cabinet hostilities towards him from either side.

A 1975 pamphlet read: “I ask you to use your vote. For it is your vote that will now decide. The Government will accept your verdict…Now the time has come for you to decide. The Government will accept your decision — whichever way it goes.”

Harold supported the ‘Yes’ campaign, keen to stay within the union, as did all other Great Offices of States holders Denis Healey (Chancellor), future successor James Callaghan (Foreign Secretary), and Roy Jenkins (Home Secretary). The ‘Yes’ side too was backed by 249/275 Conservative MPs including new leader Margaret Thatcher. All major newspapers except for The Morning Star were in the same camp.

Yet that is not to say there was no opposition. On the ‘No’ side stood future Labour leader Michael Foot who pledged in the 1983 manifesto that Britain would leave if he won and Tony Benn, who later claimed he disapproved the democratic deficit, remarking on Question Time: “Europe [is] run by bankers and commissioners who we cannot remove on polling day.” The move was also opposed by Conservative Enoch Powell and non-English parties such as the Scottish National Party (SNP), Sinn Fein, and the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP).

The vote would see a relatively mild turnout of 64.6%, with over 67% ‘Yes’ votes, with all four British nations have a majority ‘Yes’ vote. The 64+% turnout (25.9 million/40 million) may not sound too impressive but is higher when compared to modern referendums such as the 1998 Greater London Authority referendum (34%) and 2011 Alternative Vote referendum (42%).

Wilson commented the referendum was: “A free vote, without constraint, following a free democratic campaign conducted constructively and without rancour.” Wilson had brought confident for himself, a gift of policy to the people, and a participation in the political world which was lacking beforehand outside of general elections.

We now know the EU issue was not solved, culminating in something called Brexit which I don’t think the news ever mentioned…at all(!). Yet for the time, it was a success although during the Conservative-led period of 1979-1997 and the Labour-led period of 1997-2010, there were no referendums across the whole of Britain as voters would have to wait 36 years until the aforementioned AV referendum. Wilson is thus one of only two PMs to host a referendum across the whole nation.

Wilson was also a modern figure, enough to utilise the world of television. After his time as prime minister ended, Wilson has become, to date, the only PM to host a commercial television show. He hosted Friday Night, Saturday Morning; he was dreadful. Nonetheless, it is a fun look back in hindsight, creating classic television moments in a ‘so bad it’s good’ fashion. The closest since is Boris Johnson’s four occasions guest hosting Have I Got News For You before premiership.

A Case Against Britain’s Best Prime Minister: Devaluing The Pound

Whilst we make cases for Wilson, it would be remiss of us to not take a look at the negatives to his time as PM.

Spartacus Education’s John Simkin notes Wilson’s, along with Chancellor of the Exchequer Jim Callaghan’s, decision to not devalue the pound early was “Probably the biggest single blunder” post-1964 Labour government.

As alien an idea as devaluing the pound sounds to us in 2022 (wait, no it doesn’t!), such had to take place in November of 1967 after a prolonged economic plunge for the nation, exacerbated by a dockers strike and six-day Suez Canal blockade shortly beforehand. Wilson had previously been so opposed to devaluation that he outright banned any public talk of the idea, thinking it would “damage Labour politically, tarnish Britain’s international reputation and relax the economic pressures on British industry to reform and modernise itself.”

Needless to say, a devaluation situation is not what you want from the only ex-economist prime minister.

In November, the government had to bite the bullet and devalue the pound 14%, from $2.80 to $2.40 whilst interest rates raised from 6.5%-8%. This prompted a memorable ‘Pound in your Pocket’ speech, in which he stated the money currently in citizens’ banks, purses, or wallets. This was hugely criticised, including by Leader of the Opposition Edward Heath, who remarked: “It will be remembered as the most dishonest statement ever made.”

A Case Against Britain’s Best Prime Minister: EEC Failure

Mentioning the European Economic Community earlier, Wilson advocated staying into the EEC, where he initially struggled to get in.

In what would be Britain’s second attempt for entry was denied in 1967 under Wilson. In what The Guardian described as an “Emphatic ‘No’”, French President Charles de Gaulle vetoed this request. As to why, British policies and industries were deemed incompatible with the EEC as well as personal reasons for objection – notably due to Britain’s closeness to the United States meaning there would be insufficient impartiality and leaning towards the USA.

French opposition was not a new thing in the post-war era, with de Gaulle opposed to the special UK-US relationship. Churchill even said of the French president: “[He is] a Frenchman who is a bitter foe of Britain and may well bring civil war upon France.”

The BBC noted that “Only France remain[ed] opposed”, with all five other nations (Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Italy, and Germany) supporting British membership negotiations.

After General de Gaulle’s rejection, Wilson made a 16-point rebuttal, rejecting associate membership and stating the nation would still apply for full Common Market membership. This was as there was majority support after Wilson announced proposed membership in the House of the Commons on May 2nd.

This tough and stern turn-down would kill some credibility for Wilson, failing a main goal aimed for by all three major parties.

Even more annoyingly for Wilson, it would be arch-rival Edward Heath who would secure the deal. In 1969, de Gaulle stepped down and died in 1970. With this, Heath had an opening for acceptance with the opposed old guard gone. Not only was it accepted when Wilson was out of power but under terms Harold was unhappy with yet the UK nonetheless joined on January 1st 1973 alongside Ireland and Denmark.

It would then be for Wilson to deal with when back in power from 1974-1976.

A Case Against Britain’s Best Prime Minister: Public Perception

Earlier, we alluded to how a public image was so much to Wilson. It was on this image that he earned respect, admiration, and honour. However, there are those working against him, in particular the satirical magazine Private Eye and The Beatles.

To start with the latter, that name might be surprising. The Beatles? The purveyors of commercial pop hits really dragged Wilson through the mud. Well, yes.

Explained in GREAT (hopefully in both sense of the word!) detail in my Tim Minchin’s “Thank You God”: A Lyrical Over-Analysis, I note how “The Quiet Beatle” George Harrison turned against the man who had given The Beatles their silver heart medals and MBEs, writing a scathing political anthem against the 95% super-tax imposed by Wilson.

John Lennon was the one who added the named mention of Wilson, also mentioning Heath for the sake of balance. “Taxman” from the Revolver album protested with lyrics like “Should five percent appear too small/Be thankful I don’t take it all” and “Don’t ask me what I want it for”, portraying a greedy, gluttonous taxman working under Heath’s policies which punished the hard workers.

This was the literal biggest band in the world that had an immense global presence slamming domestic government policies.

Elsewhere, Private Eye was founded in 1961 and it just so happened that Wilson was one of the first PMs the magazine really took aim at.

Owned by the late, great Peter Cook, the magazine created the Mrs Wilson’s Diary column written largely by John Wells.

This gave a satirical account of the life and times of Wilson’s wife, with one reading: ‘“Enough of this bullshit’ I heard [US president] Mr Johnson’s voice exclaim on the booster, ‘when are we going to get your boys in Vietnam? Hold your horses Lady Bird [Johnson’s wife], I’ll be right back’ … Then the voice became rather muffled, and the president remarked, ‘It’s [Harold] Wilson, baby. I know, but he’s so dumb he can’t find his ass with both hands.”

Wilson was a regular front cover star with headlines reading “All the lies and smears inside!”, “Drugged with power”, and a bandaged Wilson with the headline “Should this man be kept alive?” These are admittedly more comical and deliberately bombastic as they may be to read but are not exactly a ringing endorsement of his work.

Wilson had a bad relationship with the press in general, being too vulnerable to media criticism. An example of such comes from David Dimbleby’s Yesterday’s Men documentary. An interview for the piece saw the host ask the ex-PM about how much he was asked about his memoirs he was writing.

Wilson was extremely taken aback and aggressive in response, commenting: “I’m really not having this!” and forcing the recording to be cut. Calling the question “ridiculous”, Wilson threatened Dimbleby if the interview or transcript were leaked, with Dimbleby perhaps best summing it up in the Days That Shook The BBC documentary as “a storm in a teacup.”

A Case Against Britain’s Best Prime Minister: Other Reasons For Unpopularity

The EEC issue in particular led to the Labour Party having little scope for action with an ideologically split Cabinet, paired with Wilson’s waning health at the time.

In the book Harold Wilson: The Unprincipled Prime Minister: “When he retired in 1976, ‘Wilson’s reputation was…at a low point.”

It had not helped that Wilson was now painted as a paranoid figure, in constant fear of being ‘bugged’ by MI5. Similarly, Wilson feared other attempts on his dignity, position, or life. This included the Clockwork Orange coup. According to journalist Barry Penrose, Wilson “spoke darkly of two military coups which he said had been planned to overthrow his government in the late 1960s and in the mid 1970s.” There have since been conspiracy theories of all kind that attempts have been made on Wilson and with these never being confirmed, it made Harold look like he was more and more paranoid, losing his mind, and thus questionable to be leading the nation.

There were even claims Harold Wilson was a Russian spy. An MI5 file was opened on Wilson to determine whether he was a security risk, which is enough to make anyone precautious and tentative to the PM, even if untrue.

A final sour note was Wilson’s controversial knighthood appointments. The so-called ‘Lavender List’ drew controversy. Wikipedia notes: “Some of those whom Wilson honoured included Lord Kagan, the inventor of Gannex (Wilson’s preferred raincoat), who was eventually imprisoned for fraud, and Sir Eric Miller, who later committed suicide while under police investigation for corruption.” It is also questionable the honour (OBE) given to Mike Yarwood, who carved out a career as a Harold Wilson impersonator. The likes of Roy Jenkins have commented on how lasting reputational damage was inflicted.

Epilogue

There is certainly no denying the significance of Wilson, the most important prime minister between the premierships of Winston Churchill and Margaret Thatcher. He too is arguably in the top five most significant leaders of the decade (alongside the aforementioned Churchill and Thatcher, David Lloyd George, and Tony Blair – even if the latter’s time as PM was largely conducted in the next century).

He may have been important but the best? I say yes.

Sure, Wilson, like everyone before him had shortcomings. Yet these are extremely minor compared to what Wilson saved us from and did in positive long-lasting effects. Wilson did his best to promote equality of the classes through housing, taxation, and the Open University whilst overseeing and supporting reforms that shaped the Britain that came after him for the better – in the forms of improved women, gay, and disabled rights amongst others. It would be needless to say that Britain without Wilson would be a much different and darker place. Wilson helped Britain catch up in areas they were drifting behind, bringing the nation up to date with locations in Western Europe.

In the short-term, keeping the UK officially out of Vietnam was perhaps his greatest and most pragmatic political manoeuvring whilst aiding his long-term legacy. Long-term his modernisation and strides for equality are perhaps his greatest traits. In that way, he was more reminiscent of today’s soft left Labour but nonetheless Labour through-and-through.

His upsides were so sparkling that even nemesis Edward Heath called Harold “a fine politician.” Elsewhere, The Guardian’s Geoffrey Goodman described the late Wilson as “a remarkable prime minister and, indeed, a quite remarkable man.”

Harold Wilson was not the perfect prime minister but he was looking for positive change, worked for the people, and fought, trying his best for equality and justice – and in many ways that has to make Harold Wilson Britain’s greatest prime minister.

GRIFFIN KAYE.