We have mentioned before in this series the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, acknowledging the increased slavery within the United States from the new century until the mid-19th century. One of the factors in its growth was the invention of the cotton gin. Just how did an anti-slavery Yale graduate try to aid slaves but instead create an invention that quadrupled slavery numbers, tripled slavery states, and sped up the road to the American Civil War?

Eli Whitney: Inventing The Cotton Gin

Eli Whitney had plans of becoming a lawyer prior to his creation of the cotton gin.

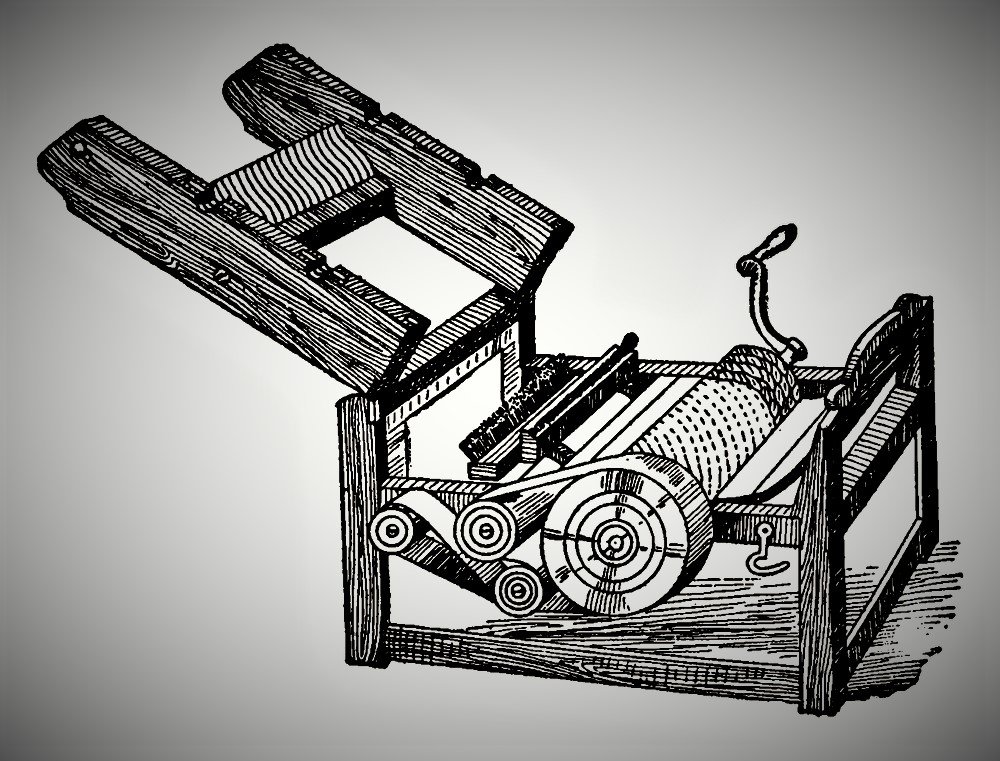

The cotton gin – short for ‘engine’ – was developed after the Massachusetts-born Whitney was told by landlady Catharine Green about the issues of cotton production.

See, the only inland cotton that could be grown was green-seed cotton, which contained seeds that would be time-consuming for removal. Just removing a pound of the lint from short-staple cotton would be a good amount per day. Eli hoped that his invention could quash slavery with no longer any need for mass seed removal, thus ending the already-dying market of slavery.

Without going into too great deal, the machine worked with a wooden drum with hooks that could catch the fibres and gift out seedless cotton. All fibres were too big to pass through and thus caught and removed. The Encyclopedia Britannica states: “Whitney’s cotton gin had four parts: (1) a hopper to feed the cotton into the gin; (2) a revolving cylinder studded with hundreds of short wire hooks, closely set in ordered lines to match fine grooves cut in (3) a stationary breastwork that strained out the seed while the fibre flowed through; and (4) a clearer, which was a cylinder set with bristles, turning in the opposite direction, that brushed the cotton from the hooks and let it fly off by its own centrifugal force.”

The machine process itself required minimal work with a simple hand-cranking or attaching to an alternate energy supply (i.e. moving horse, water wheel, etc.).

Whitney created and patented the machine in 1794.

Side Effects

The cotton gin was extremely impressive, able to do the same amount of work as 50 slaves, able to remove 50 pounds of cotton per day.

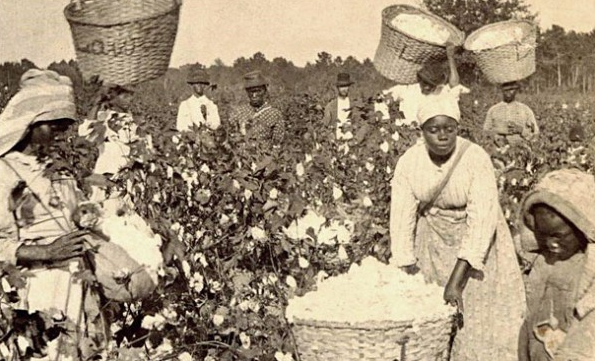

Whilst this would work to stop slaves removing cotton lints and fibres, the cotton-picking industry grew massively. Now more profitable, farm owners extended profits by growing land and as a result needing more slaves to pick the cotton.

Over the next 60 years, slavery grew drastically. The invention backfired, with the statistics speaking for themselves.

An Increase In Slavery

In 1790, a few years prior to the cotton gin’s invention, there were six slavery states with 700,000 slaves; in 1850, 15 states saw 3,000,000 slaves.

The National Archives adds “After the invention of the cotton gin, the yield of raw cotton doubled each decade after 1800”, showing slavery’s rise at an immense pace.

The website ThoughtCo. Adds that US cotton exports grew from less than 500,000 in 1973 to 93,000,000 by 1810, as “cotton soon became America’s main export, representing over half the value of the US exports from 1820 to 1860.” By 1860, it represented 57% of all American exports with 5,000,000 bales a year. In 1800, only 7% of exports were in cotton.

As author Angela Lakwete commented in her 2005 book Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America, cotton gin was an “integral factor…in the development of a slave labour-based southern economy.”

Not Money For Nothing

Despite doing the invert of his intentions at least Whitney could make some profit, utilising his 1794 patent, right? Well, about that…

In a letter to his father, Eli even said “’Tis generally said by those who know anything about it, that I shall make a fortune by it.”

Yet the patent office was very flawed prior to 1800 reforms. This meant protection was often weak. The gin was not to be sold commercially but farmers would be charged to use the machine, for around two-fifths of the profit. Unhappy at this, many made facsimiles yet legal loopholes allowed the farmers to make replicas without legal ramifications and Whitney’s inability to do anything about it.

This meant Whitney basically made nothing off of the invention.

In reaction, Whitney claimed about a decade later: “an invention can be so valuable as to be worthless to the inventor.”

Not only had he set the stage for slavery and cultural divide but had done no better out of it – a truly cruel fate for a man who wanted to help the world but instead laid the foundation for a more concentrated era of hardship, regression, and sorrow.

Epilogue

Did the cotton gin cause the American Civil War? It would be entirely monocausal and simplistic to say that slavery, let alone Whitney, caused the chaos that unfolded from 1861-1865 under Abraham Lincoln. Brother turned on brother as the Union fought the Confederacy in a war largely fuelled by slavery, an issue undoubtedly exacerbated and expanded by Whitney’s invention.

In the modern era, we look at far more trivial inventions such as New Coke, Clippy, and Crocs as horribly misfiring blunders. How, I ask, can we realistically compel these to history in the same way as an invention ruined at least 2,300,000 lives? This is on top of the families of slaves, the deaths of the Civil War, and not to mention Whitney whose guilty conscience must have spectred him in his lifetime, even if not living to see the peak of slavery in the south.

Perhaps the really harsh thing about the invention is the innocent lives it ruined. Eli’s is one, but what about the others who found themselves living a life of bleakness and deprivation that they likely would have lived without had it not been for the creation from Whitney’s hands.

In Whitney’s own prophetic words: “I have now taken a serious task upon myself and I fear a greater one that is in the power of any man to perform in the given time, but it is too late to go back.”

GRIFFIN KAYE.