As I currently stream my comfort shows across an array of streaming services, it seems as though my cable subscription remains solely to watch the Rays locally in the Tampa Bay area, 1AM insomniac-driven reruns of America Says on the Game Show Network, and to see whatever antics Becky Lynch gets into that week on the USA Network. Despite a stranglehold on television for generations, cord-cutting has become a popular phenomenon as streaming demand has increased to a higher level than ever, and the people who seem to be keeping cable do so for the reasons I do.

There are a plethora of reasons that both cable and broadcast television finds themselves behind the 8-ball and struggling to get out in front, yet as mainstream television continues to deal with an evolving-market in an everchanging world, its replacement seems to already be hitting walls of its own. A lot of discourse surrounding streaming and cable as of late on platforms such as Twitter and Reddit indicate a growing feeling that streaming is becoming a cable model, a full-circle moment of consumerism in the United States. Unfortunately, even with services consolidating, introducing ad-tiers, and cancelling some of its most important shows, the conversation lacks total nuance that looks only at price, and does so incorrectly. Both have an abundance of problems heading into 2024, but are entirely different in every possible way.

Traditional Television’s Antiquated Model Just Can’t Offer Convenience For Price

The highest rated show on television in 1960 was Gunsmoke, airing on broadcast television in a time when only an approximated 45 million households had a television. All in the Family, the brainchild of the recently departed Norman Lear, was the #1 show on television in the first six years of its nine-season run from 1971-1976 on CBS. 1976, when an estimated 90% of America had television, marked the first year of the WTBS superstation. WTBS Superstation, now known as TBS, was the first cable giant built around Warner’s acquisition of the Atlanta Braves. By the 1980s, cable had taken over entirely with around 53 million households having cable by the end of the decade. Yet, after dominating household entertainment, shows on broadcast and cable networks seem to be a dying breed.

The highest-rated show on CBS in 2022 was Ghosts, a Rose McIver-led ensemble sitcom where her character can communicate with ghosts that died on her property. The show garnered an average of nine million viewers per episode, a far cry from the ratings garnered by Gunsmoke or All in the Family in a time when televisions were in fewer households and access to media was far more restricted. The highest overall show on broadcast television happened to be Sunday Night Football on NBC for the sixth consecutive year, showing that viewers would rather watch Micah Parsons or Antoine Winfield Jr. eat up offenses around the league than any television show offered in primetime in real time. With more households cancelling cable and stunningly low ratings across the board, live content you must tune in or miss, such as sports, seem to be the biggest draw on not only broadcast television, but cable television.

Tony Khan’s Pro Wrestling upstart All Elite Wrestling is consistently in the top three in a primetime, Wednesday night timeslot despite regularly drawing under a million live viewers. TBS’ highest-rated active show in 2023 surrounds characters such as an anxious millennial cowboy, a real-life dinosaur, an Ashanti Prince, and a 1950s thespian who turns everything around her into black and white as if she’s Gloria Swanson in Sunset Blvd, all under the context of sports and competition. It’s a market where the biggest premium cable channels are ESPN because of the NHL and TNT because of the NBA. While many subscription services such as Peacock, Amazon Prime, and MAX are beginning to add live sports to gain an advantage in streaming medium, blackout restrictions exist because cable needs them to survive, even with most premium regional sports channels such as Sinclair filing for bankruptcy.

The model of cable built on syndication doesn’t hold much weight anymore. Typically, shows enter syndication after 88 episodes, with four seasons of the traditional 22-episode format. 100 is usually the goal for the minimum, as that makes a show prime for stripped syndication money. However, certain shows are sold well-below that threshold and see success, such as Arrested Development and the Jetsons, at 84 and 75 episodes, respectively. Syndicated moneymakers such as Seinfeld, Friends, and the Office have been a major selling point for the cable alternative. Seinfeld has a $500MM streaming rights contract with Netflix while MAX and Peacock used the latter two shows that Warner and NBCUniversal already owned in-house to nab consumers, respectively. The cheapest Spectrum cable package starts at $60 a month before applicable taxes, which is more than MAX, Netflix, Peacock and Disney+ per month combined before applicable taxes. While cost of streaming continues to go up leading to some to suspect consumers to return to a one-price cable bill, it doesn’t consider that the young generation that still watches cable does it almost entirely for live sports and the cable viewing habits of the older generations tends to stick to either CNN’s Anderson Cooper or FOX’s Jesse Watters, depending on their political identity. Overall, if viewers don’t have a vested interest in sports or politics, then they’re still unlikely to go back.

For the same price, the consumer will still have near-unfiltered access to television shows of their choosing 24/7, with the ability to choose the specific episode that they want and doing so without advertisements. The ability to cherry pick premium channels instead of being given a blanket of 150 channels in which the average viewer will regularly use maybe five directly limits their options in a way that streaming doesn’t. Under the cable model, viewers would have to seek out the nostalgic shows they want to watch. For example, if a viewer were to want to watch King of Queens for the first time because the recently-viral Doug Heffernan meme exposed them to a new show, they’d have to jump in on whatever syndicated episode that TVLand is showing on a late-Friday night, as opposed to be being able to go to their Peacock app and starting from Jerry Stiller burning down his house in the pilot. The other thing that cable’s model cannot account for is how useful an algorithm can be to continue watching, because following the binge-watch of King of Queens, Peacock can (and does) immediately recommend Everybody Loves Raymond, a show that regularly crossed over with King of Queens.

Cable tried to compete with the streaming model by adding premium channels. AT&T, for instance, once offered an add-on premium channel called Audience that included original content such as Mr. Mercedes. It was this kind of model that HBO original became known as in its golden era, delivering a variety of content such as political dramedy The West Wing, mob hit The Sopranos, the late-night Larry Sanders Show, and Kristin Davis romance classic Sex and the City.

The Benefits of Streaming Create Their Own Surplus of Problems

As Viacom sets to fully consolidate their Paramount+ service with Showtime, a service that at one point was an innovator in the streaming game, it puts forth a look into a bleaker future of streaming. In the current streaming landscape, more streaming services are being threatened via their revenue streams, or lack thereof. As the streaming bubble expanded with every studio and niche company creating their own, it fostered an environment where the supply surpassed the demand. We’ve seen quite a bit of consolidation in recent years for the more niche interests: the WWE Network landing on Peacock, Studio Ghibli landing on MAX, as well as the Funimation merger with Crunchyroll. The bigger services are starting to merge with their sister platforms, as WarnerMedia has already rolled out its merger of HBOMax and Discovery+, while Disney is set to merge Disney+ with Hulu in 2024. Disney is already beta-testing the new app, as well as airing upcoming content on both services. The most notable upcoming project to stream on both services will be the new Percy Jackson and the Olympians series, starring Leah Jeffries, Walker Scobell, Adam Copeland, and the late Lance Reddick.

I’m typing this with the SyFy original 12 Monkeys series starring Amanda Schull in the background on Hulu, a show I didn’t discover until after it was off-air during the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s primarily what I use streaming for at this point: discovering or re-visiting shows that are already off the air. I don’t seem to be alone in the sentiment, as it was Suits, the show that made the aforementioned Amanda Schull famous for portraying Katrina Bennett, that ended up being the most watched show in the history of Netflix this summer. Suits not only has the most minutes of any show watched over the course of a summer in streaming history, but also most weeks as the number one show streamed in the world, per Nielsen metrics. The show ended before the pandemic, isn’t on Netflix in its entirety and is still demolishing its ongoing original programming that has higher budgets and an A-List cast.

The Suits explosion seems to coincide with three primary things: the release of Netflix’s Meghan Markle documentary, who portrayed Rachel Zane in the first seven seasons of the USA original, the writer’s strike limiting the production of other shows, but also the nostalgic feel for a now-antiquated way of watching television. The third reason seems to be the upcoming problem that Netflix and its streaming rivals must tackle head on going forward: not everything has to be a binge.

Stranger Things is undoubtedly Netflix’s biggest original series. Yet, it encompasses a primary reason for the change in how Netflix produces its show beyond the quality of the content. According to Antenna’s market research, a vast majority of the people who set records in 2022 watching the program churned Netflix after. In a nutshell, there’s a lot of consumer turnover because consumers will subscribe for a week, binge, and cancel. This type of consumer makes it difficult for Netflix’s stock dividends, or any streaming service’s dividends, altering how they produce content.

Keeping people binging is the primary concern. Television used to be a past time. If you watched an episode of Friends and you’re joining in on the middle of a season seven episode with zero context, you don’t exactly need to know Joey’s backstory when he joins Rachel and Chandler in eating cheesecake off of the floor at the end of the episode to see the humor in it. That era of television made with mindless enjoyment and white noise intentions is a thing of the past. The story must suck you in, with enough content to keep you watching as long as possible. Then, after, once you like it, an algorithm will recommend something similar to get you to watch another show that features commitment. This is one of a few reasons that syndicated television is a thing of the past, a negative for the cable model, which we’ll get to in this deep dive eventually.

If shows don’t take off the way that Orange is the New Black did for Netflix a decade ago or Stranger Things did in the later part of the same decade, streaming services will usually opt to do one of two things: cancel the show and green light new shows or eat the money on another season for a tax write-off. Each has their own situational purpose, the other being such a nuanced financial decision that’s above my paygrade to explain. But they could explain it, because as Kramer so eloquently points out in season eight of Seinfeld, they’re the ones writing it off. The issue is that very few shows reach that stratosphere, especially these days. At the height of cable, there would be 20 to 30 shows that would get tens of millions live, much less those who VCR’d the program, on TV regularly in any given time period. The vintage ‘water cooler’ television talks don’t exist anymore with how precise algorithms are. Each person has different tastes and there’s content tailored toward each individual interest, creating mass-individualism within television. For a consumer, it’s a good thing, but for marketing, it’s a nightmare to cater shows to a mass audience to gain every single set of eyeballs. If you have every option you can imagine available, then a mainstream audience is going to be split everywhere.

The idea of a mainstream audience has been out there as long as media has existed, but the existence of one has been dwindling for years. In a world of unfiltered access to any interest, channel surfing and watching whatever is in the primetime spot isn’t a thing. You cannot create a television beast in the same way that you did years ago. This becomes more difficult in a world where the only proven moneymakers are established franchises. Disney+, for example, has built all of their new content around Star Wars and Marvel. They’re going to retain people because of their content library, regardless. It’s been reported that the most watched content when Disney+ dropped were older Disney Channel cartoons such as Gargoyles and Kim Possible, but films such as Oliver and Co. and The Hunchback of Notre Dame have seen a marketing resurgence because Disney noticed how many people flocked toward the less-pushed content in their video library. For the most part, Disney should have a good retention rate, and this isn’t exactly a criticism of their model as they’re poised to be the top streamer in the game for the foreseeable future. However, their highest rated original shows since the start of the platform in 2019 are The Mandalorian and WandaVision. Unfortunately, these shows seem to have a steep drop-off in viewership since. The Mandalorian saw a concerningly drastic drop in viewership between season two and season three. To fully be caught up in the storyline to understand season three, viewers would have to have seen the Book of Boba Fett in its entirety, seeing as Din Djarin and Grogu’s arc are a major part of both that series, and of course, season three of the Mandalorian (a show based on Djarin and Grogu). Disney+ has also suffered similar consequences with WandaVision and its slew of Marvel television counterparts. It’s an unsustainable model of television because it’s unreasonable to expect a vast majority of your audience to dedicate their time to every single show you produce just to be able to understand a show that they enjoy. Viewership time is finite and its an oversaturated market where they can and will find other things to enjoy than sitting through content they may not enjoy or have time for just to be able to enjoy something else.

Television universes aren’t a new thing. The previously mentioned All in the Family encompassed a spinoff tree that featured Maude, Good Times, The Jeffersons, Archie Bunker’s Place, and three other spinoffs. Most major television successes receive them. For Happy Days fans, Larverne and Shirley was a welcome continuation of that ilk. Yet, Penny Marshall appeared in a total of five episodes of Happy Days and none of them flesh out the Laverne DeFazio character enough to where audiences of Laverne and Shirley miss out on integral character development. Netflix’s model accounts for spinoffs. In 2023, Netflix aired That ’90s Show, taking place 20 years following the events of late-’90s sitcom That ’70s Show. Netflix, as of this past week, has reportedly greenlit the creation of spinoffs to Wednesday and Peaky Blinders, continuing to use as much of the IP they own of successful shows that they can. However, it remains to be seen if they’re going to follow in the footsteps of Disney and make watching the original a requirement. For Peaky Blinders, the series ended in the first quarter of 2022, so major storylines in the on-going show won’t be a problem to present itself, but the same can’t be said for Wednesday. Season two of Wednesday is set to film in April of 2024, and depending on if Netflix continues to produce the show and the start of the future spinoff, that will be the first real litmus test of another streaming service following Disney’s strategy at the expense of its viewers.

The other criticism of these style of television show isn’t just how much additional television you have to watch, but the volume of just one show, mixed with when you watch them. When a television show, and all current streaming services are building their brand around them, wants to be an eight hour movie with a million-dollar-per-episode budget and an A-list cast, it creates two discrepancies in making television: a lack of easy-to-stomach time killers and shows that will cost more money than they bring to the studio. We aren’t making television like television anymore. The reason sitcoms are timeless through generation isn’t because they’re for those who can’t think, they’re for those who don’t want to think. The age-old criticism that these shows are mindless drivel misses the point that television is entertainment, and sometimes people turn to entertainment for something they don’t have to think about to enjoy.

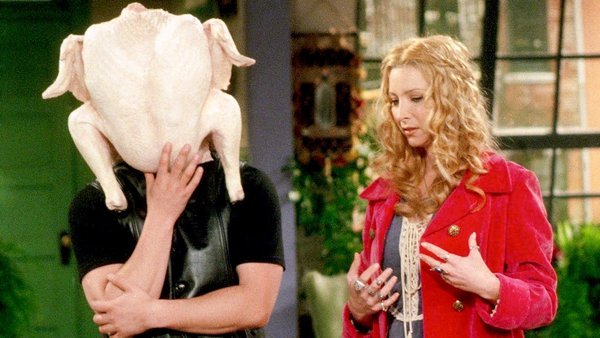

Sitcoms don’t exactly offer the most intriguing storylines to follow. Yet, there’s a reason a show like Friends has been so successful on live television for ten years, syndication for 25, and streaming for as long as it’s been available. Friends has made billions in syndication since it attained it in it in 1998, currently still the highest grossing syndicated television show as it airs on stations such as TBS and Nick at Nite. The ability to jump in on a random episode as noted earlier is crucial to syndication. If a show, such as HBO’s Last of Us, one of the biggest shows of 2023, were to air a random episode, it’s unlikely that a viewer would be able to follow the episode without the context provided in other episodes. Shows in the past, such as Prison Break and Supernatural, offered a ‘previously on’ segment at the top of the episode to balance this issue out, yet these are shows that following the overall arc can be important, but are written in a way that they regularly provide the context throughout the future episodes. Shows designed specifically to binge don’t do such a thing.

The Last of Us also average $12M per budget per episode last season. To get to the money found through cable with syndication, they’d have spend a number of more seasons at the same budget and many years after that trying to match their budget in syndication. These shows are built strictly for streaming with the intent of luring in the viewer enough to maintain subscriptions and garner new subscriptions, yet the model is a bubble that’s nearing a major pop because there’s only a finite amount of subscriptions available for demand, and everything has to go right to break even.

This can be unfortunate because every show gets a marquee budget on streaming with the value that studios believe that the modern television viewer puts on ‘production value.’ Shows cannot feel cheap, and it becomes easier to throw money at the shows than to get creative within a budget. That also doesn’t give shows at least three seasons to hit a stride like television shows used to do. If a show doesn’t take off, studios will look at their shows and stops airing episodes as aforementioned, consumers lose trust that their favorite shows will continue, leading to a mindset of not watching television until it’s off air.

The final major issue with shows being cancelled is from a consumerism perspective. Starz, for example, is cancelling Shining Vale this month. The horror show starring Courteney Cox is a Starz original, but will be removed from the service entirely. While streaming can lead to the discovery of what was thought to be less media, it can lead to more as well as it is often more cost-efficient to not use space in the cloud to keep content companies own the rights to on the platform. With streaming ending the widespread sale of DVDs and newer shows being unlikely to get released as physical media, fans of the show will lose access to these programs altogether.

These Problems in the Current Market

Projecting the future of these problems and how to fix them is above my paygrade, but streaming should be beating cable in a landslide. The lack of ads on certain services and a smaller frequency on all, the ability to watch on any device, more options in the content you indulge in, and the fact that you get to choose when to watch something is a television fanatic’s paradise that cable simply cannot compete with.

Yet, consumers are fatigued. Every studio has their own service and are constantly upping the price because of overinflated stocks combined with a concoction of questionable algorithm techniques, larger budgets, and a bubble business model on the verge of bursting. The only streaming service that doesn’t regularly cry poor is Amazon Prime, yet that’s primarily due to their retail model as the streaming service provides little-to-no impact on the bottom, though that may change with the reported ad-free tier being added.

As streaming services merge, that’s going to solve problems while causing different problems altogether. But, for many services, it’s becoming a must as despite profits, shareholders demand constant improvement, leading to as many strategies as possible to improve the stock, even if it leads (and it does, as proven in the market) to services operating in the red instead of the green. Not to mention, navigating consumer fatigue is big issue. When streaming began, almost all content could be found curated on Netflix or Showtime, but as the monopoly busted, so did the curation. Streamers now navigate through so many services just to find a show that they want to watch that it became a chore in time, according to a 2022 Accenture study. Approximately 60% of streamers jump from one subscription to another based on their monthly offerings, while also feeling that at least half the content services offer don’t cater to them.

The services offer something for everybody and not a single person watched every single cable channel they paid for with cable, so I’d rather not write a diatribe on the streaming services for the latter portion of that study, as it’s a tad absurd. But, the streamers jumping from one subscription to another leads to an awful customer retention rate that’s crucial to shareholder confidence, making an already-unsustainable business model even more volatile.

However, the constant cry on social media that we’re ‘returning to cable’ is objectively not true. In a world where the cost of most things are rising, entertainment has gotten significantly cheaper. For somebody like me who watches more television than most, the price isn’t exactly relevant. Yet, somebody who is more conscientious about it can find the services their favorite shows are. As mentioned earlier, Netflix, MAX, Disney+ and Peacock are a total of less than $60 a month before taxes. At its peak, you had to pay more than that price for your cable package, plus a monthly fee for each box in the house and each DVR, while having significantly less say in when and what you watch, and how you watch it.

With how strong U.S. infrastructure is, especially in the broadcasting realm, live television will always exist at least for broadcast appeal, but cable doesn’t have the same safety net, despite similar staying power. For cable, the hope must remain in two very specific markets that keep the consumer coming back: live sports. Yet, that may be on borrowed time seeing as Sinclair recently filed for bankruptcy, killing the regional sports market instantaneously. MLB, for example, has the strictest blackout restrictions in sports, yet the Padres became the first of now-many teams to be dropped by the regional network and move solely to MLB’s MLB.tv service. Slowly, teams around the league are starting to become league produced as well.

The death of cable seems to be slow, if not non-existent. The cable companies can’t keep up, but there’s still a larger number of cable customers than most probably realize. There’s always going to be some kind of market for live programming that you don’t have to think about or go out of your way for, even if it doesn’t re-invent the wheel and is no longer the industry leader. Perhaps, the end game for the cable providers that haven’t made the streaming pivot and don’t have the marketplace to do so is in being acquired by a larger company, a la an Amazon or Apple, but even then the appeal in purchasing those channels would be in using the cable market to supplement their other content. For example, Disney started airing Hulu original Only Murders in the Building with Selena Gomez and Steve Martin this week on ABC. Disney seems to be ahead of the curve in the market place usually, so perhaps using shows with major marketing power to supplement the cable channel will bring eyes that don’t want to subscribe to Hulu to their primary television channel, opening both their original content and channel to new eyes.

The other way that television companies are staying on traditional television is live formatting. With the success of live sports and live news, it’s telling that the two things that constantly get people to tune in are things that are immediately spoiled should you open Facebook or TikTok while you’re out. This has led to an influx of shows such as The Masked Singer and The Voice being the trend, since the competition-based format makes it so a viewer has to watch or they find out either who’s under the mask or if Gwen Stefani’s turned-her-chair. This most likely will make up the money they’re losing as the consumerism of cable dies down through fewer production costs with making a live studio show as opposed to a high-budget television drama.

Television has an upcoming 2024 that should determine more of the future direction in the industry. For viewers, they have more options than ever. For studios, decisions have to be made. Suffice to say, the industry is in an awkward phase right now, and it’s undetermined whether its next phase is for better or for worse, so for now, let’s enjoy the sheer volume of high quality content at our fingertips.